Anorexia and Dance. Looking for the perfect body in dance!

As dancers we are constantly judging ourselves: spending hours day after day in tight-fitting clothing in front of a mirror and scrutinising how we look. Dancers are expected to have slim and toned bodies. It is seen as particularly important for females to be of a slight stature for the ease of pas de deux and partnering work. But what is the impact? “The average incidence of eating disorders in the white middle-class population is 1 in 100. In classical ballet, it is one in five” says Dr Michelle Warren, an eating disorder specialist.

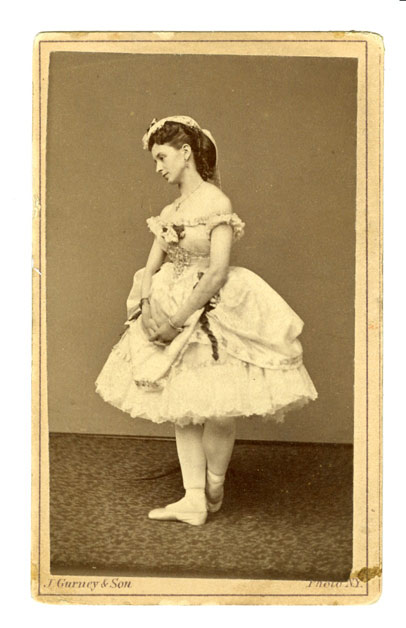

However, the ideal dancer’s physique hasn’t always favoured the slim. A century ago, the ballets and dance works of the time were biased towards the story-telling and dramatic elements of dance and therefore softer, rounder, and more delicate features were desired. Yet as the 1920s brought with them the flapper dress, the ‘androgynous body’ became fashionable often describing females as ‘waifs’: with skinny, willowy limbs. Soon abstraction and a focus towards favouring line and shape, spear-headed by the choreographer George Balanchine, took hold and dancers with a slim physique were favoured. Previously lavish costumes became minimal leotards and therefore an aesthetic towards little or no body fat became the norm.

A dancer’s world is one of control. ”People attracted to dance may be looking for that kind of structure,” says Marijeanne Liederbach, director of research and education at the Harkness Center for Dance Injuries in Manhattan. ”Achieving a triple pirouette or 105 on the scale are tangible goals in a difficult world.” Anorexia, or Anorexia Nervosa, is defined (by BEAT) as: “a serious mental illness where people keep their body weight low by dieting, vomiting, using laxatives or excessively exercising”. This definition is characterised mainly by symptoms of the disease. However, what is interesting is that the dictionary definition for ‘perfect’ seems to draw eerily close parallels to how sufferers have described that they feel. Perfect is defined as: “conforming absolutely to the description or definition of an ideal type; excellent or complete beyond practical or theoretical improvement”. Perfection is a term often used in dance and many dancers strive for the ‘perfect physique’, but this can quickly become destructive. Sufferers of Anorexia have a distorted image of themselves; they look in the mirror and see a fat person, when in actual fact the opposite is true.

The feeling of control, or rather loss of control, was one of the main concerns for Margherita Barbieri, a young dancer who battled with Anorexia for four years. She says, “my eating disorder had become my identity”. She was moody, aggressive, verbally and physically violent, and obsessed over calorie counting and exercise: behaviours that surprised even her. Talking to Margi it is clear that the tough environment of the dance world was the trigger in allowing Anorexia to take hold: she describes it as, “your genetics load the eating disorder gun, but the environment pulls the trigger”.

Unfortunately, after failing to be accepted into Senior Associates at The Royal Ballet School, she was ‘reassured’ that it was because of her physique rather than lack of technique. According to Margherita she was given remarks such as ‘too muscular’ and ‘oversized’ to describe her physique. To be told that your body is too muscular seems contradictory in a profession that demands an athlete’s strength and muscular power. It leads us to the wrong way of thinking when it comes to a dancer’s physique. Still, the trigger of the loaded gun had been pulled and it was quick-fire from then on. Just 4-5 weeks later on her 14th birthday Margi had already lost 5kg and had eaten only a ‘handful of times’. Despite this she was accepted into Elmhurst School of Ballet and placed into an even more intense dance environment where she (or namely Anorexia) had total control over her eating habits.

For 3 years she simply ‘went along’ to therapy sessions. It was only when as a new 18 year old and an adult, that she really embraced therapy. She wanted to recover. Margherita realised that Anorexia had stopped her developing into a woman: she was an adult trapped in a 12 year old’s body. Unable to complete her GCSE’s and having to leave Elmhurst School of Ballet, she had no femininity, social life, dance career or independence to speak of. “When I remembered all those things of why I needed to recover, the process of recovery became something I wanted and it became a million times easier”.

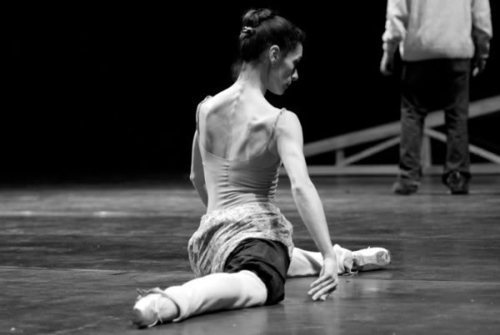

Right photo by ©Miro Arva.

Margherita speaks of ‘making the split’ as one of the most important moments of realisation in her recovery. “Identify ‘Ana’ as being separate from you and discover yourself.” In this way you make your own decisions, including the decision to recover and wave goodbye to ‘Ana’. In recovery and when therapy ends, Margi says that finding a community on Instagram and creating the hashtag #margisarmy has helped with maintaining her healthy outlook. But how can we help? It is important, especially for dance companies and institutions, to be aware of a dancer’s background so that appropriate support and safeguarding can be put in place. Mental health is a complicated homeostasis: any other things a sufferer is experiencing can exacerbate or improve their condition. It is important to conceptualise what is maintaining their eating disorder and work from there. What is underlying? Is it self-esteem, anxiety, depression? Preferably, prevention methods should be sought and applied before Anorexia can even take hold.

Rachel Bar, manager of Health and Research Initiatives at Canada’s National Ballet School has conducted research specific to eating disorder prevention in athletes. She explains that recovery practices such as CBT have no more than a 50% success rate for Anorexia; it is a difficult disease to treat and so instead she urges the focus on prevention. Anorexia is often seen as the individuals’ problem, but by instead implementing systematic changes to an environment as a whole it removes the trigger aspect of the loaded eating disorder gun. Examples of this: don’t weigh the students; don’t deliver personal corrections and comments.

Rachel has noticed evolution in a positive direction at Canada’s National Ballet School since the time she was a student there, particularly by looking at the messaging and modelling for the students. It is paramount that dancers are getting proper nutrition education (at the calibre of professional athletes) and are ultimately living well so that long term health issues are minimised and sustainability of the body is maximised. Being a dancer has huge health benefits and it is often taken for granted. It is a positive thing that dancers are thoughtful about what they put into their bodies and how they use their bodies. Being so active and able can have great positive effects on body image and should be celebrated. Changing the mind-set is the key to prevention. “Eating disorders is still not a ‘safe word’, but it is in our interests to talk about mental health with our dancers” says Rachel. Dance is a stressful and competitive environment and we can’t afford a world where it is still taboo to talk about eating disorders.

With thanks to:

Rachel Bar – her review paper is published in The European Journal of Sports Science, titled: Eating disorder prevention initiatives for athletes: A review

Margherita Barbieri has appeared on:

- BBC Berkshire radio for ‘Mental Health Awareness Week’ (October 2016)

- BBC South today morning news (20th October 2016) with a short video clip of herself talking about the dangers of anorexia

- Daily Mail News online (14th October 2016): described her story and how self-esteem is the lead cause of anorexia

- Follow her on Instagram: @alwaysmargi https://www.instagram.com/alwaysmargi/

- Anorexia and Dance. Looking for the perfect body in dance! - July 6, 2019

- Save their souls: The importance of dance and the arts for young people - July 4, 2019

- In the in-between…how to survive between dance contracts - July 3, 2019