Being (il)legal #1: A Personal Account of an American Dancer in Europe

Sorry, that is not in my jurisdiction.

Sorry, without a Model A Registration Card, we cannot take your application.

I’m sorry, I’m afraid you are going to have to go back to the US and apply from there.

—

Being a foreign freelance artist is difficult in Europe. As a dance artist, I want to base myself in Brussels. More than Berlin and London, this is where I feel most accepted, most inspired, most intrigued, most challenged, most supported. And for what?–– For my art, my research and practice.

I have spent the last three months expending countless hours of energy trying to navigate the Belgian bureaucratic system. This has sent me bouncing, virtually, from websites representing Brussels and Flanders (not even looking into Wallonia, because yes, Belgium has not three, but four different parliaments), and, physically, from communes to artist consultants to legal consultants to an enterprise counter to the internal office and to the work permit office. While I never received a full answer for anything, I kept pushing.

Unfortunately, that whole ‘90 days within a 180-day period’ visa-free travel has come to a close. While the system has partially defeated me, this wasn’t for nothing.

Let’s backtrack.

I moved to Berlin in 2014, after graduating from the University of New Mexico. I first received a “Looking for Work” visa that lasted for six months. Within these six months, I applied to many bars, restaurants, and cafes – always turned down because I didn’t speak German. Fair enough. Within this time, I applied for many auditions but hardly received invitations. Grinning and bearing, I got a contract to be in the corps de ballet for Eugene Onegin with Deutsche Oper Berlin for the spring of 2015. (I label myself as a contemporary dance artist). Nonetheless, this opportunity gave me two visas – an interim visa between the expiry of my “Looking for Work” visa and the actual full fledged 56-day working visa.

Within these 56 days of Eugene Onegin, I was accepted into Transitions Dance Company – a graduate company under Trinity Laban Conservatoire of Music & Dance – in London. Thus, I was granted a six-month “non-working” German visa to pass the time until I moved to London. While these six months eliminated any border hassles, I still could not legally work.

August 2015 came around. I was given a UK student visa restricted to a 20-hours-per-week working limit as an “employee” only, not as an “entertainer” – which is apparently what the UK (and many other) governments think is all we do: entertain. So I worked in a bar as an employee.

In the summer of 2016, I was offered a project with Luke Brown to work on his most recent work For You I Long the Longest – a dance theater work that used Brown’s upbringing to shine a light on the struggles of dwindling low- to middle-class British society. Not only did I want an artistically engaging job, but I wanted to work with these fantastic people. The project required me to be a freelance “entertainer”.

Because being a freelancer was not possible on my visa, my first option was to be sponsored through Trinity Laban where I was still a student working on my final thesis.

Sorry, we cannot sponsor you because it is not written within your course guidelines.

Option two: the “Exceptional Talent” card.

In the UK, you must be fully sponsored – either by an established company willing to also jump through hoops, pay a lot of money, and break through the red tape, or by your own sheer genius of talent as seen by an Academy Award, BAFTA, Golden Globe or Emmy, Grammy, Oscar, or Tony (EGOT) nomination.

under Tier 1 (Exceptional Talent) – GOV.UK (page 26.)

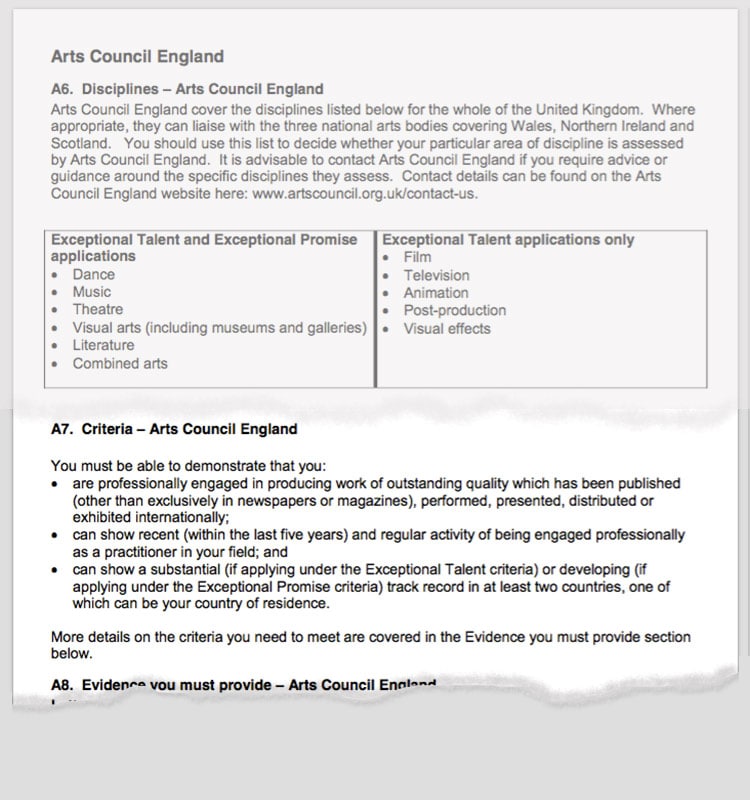

If you have not been sponsored by a specific company because they are too small to do so, yet you still want to be eligible for any freelance work, there is one way you could potentially get non-EGOT sponsorship through what the UK calls a Tier 1 (Exceptional Talent) visa. While you will still need a sponsor, it doesn’t have to be one particular company. In this case, Arts Council England has been allotted 250 sponsorships per year by the U.K. government to be issued to artists of all mediums (fingers crossed this holds with whichever way the UK snap election turns).

If you are to download and read all the fine print here, you’ll understand my next reaction to their strict requirements.

Are you bloody kidding me? I just came out of graduate school. I was in one “international” work – Eugene Onegin. I am no special prodigy just like the majority of artists aren’t. We are humans who have the drive to create and whose countries do not provide the means to do so. You are educating me, getting thousands of pounds out of it, restricting my possibilities, and then kicking me out of your country.

So I left the UK for Belgium – entering into my sixth European visa within two and a half years.

Current State

My time spent in Brussels allowed me to meet many local artists and attend auditions in or near the area. The community is rich and vibrant – offering me two projects whilst there.

One of these projects is set for this summer with keski.e.space. I thought this project would meet the requirements for an ‘Artiste de Spectacle’ work permit which would give me three months to work on the project without needing a long-term visa; however, the project doesn’t meet the minimum payment requirements set by the Belgian government and is supposed to tour for two years off and on – as many works here in Belgium do.

Belgium is tiny – many of its most successful artists from abroad. So I still ask how there is such a disconnect between artistic funding bodies and the offices in charge of foreign work permits. Something needs to change and processes need streamlining.

While I write this from my hometown of Albuquerque and say tot ziens and au revoir to Belgium temporarily, the loops and hoops continue. It’s time to reenergize and come back more organized and ready.

—

Being (il)legal is a multi-part series looking at foreigners pushing the legal limits to pursue their art in Europe. Taking triumphs, failures, and the ambiguous in-between, we attempt to expose bureaucratic feats.

Read the previous article of the series:

Being (il)legal: Preface | A multi-part series looking at foreigner’s pushing the legal limits to pursue their art in Europe